Making family memories: the Plucker Barn in Walla Walla County restored

The fully rehabilitated Plucker Barn painted in “Heritage Red.”

By Ron Plucker

Washington State’s Heritage Barn Initiative has helped many families in the state save what is arguably the most historically significant structure they have. One superb example is that of the Plucker Family Farm barn in Walla Walla County. The farm was homesteaded by Charles Plucker in 1875. Charles had immigrated to the United States in the 1850s, joined the U.S. Army, and was sent west to Fort Simcoe near what is now Yakima. Upon his discharge in 1861, he settled in Walla Walla and became one of the city’s founding fathers, operating a successful painting business before finally settling on the homestead, 12 miles north of Touchet on the Touchet River.

The Plucker Homestead property includes the sites of a number of historically significant events. On April 30, 1806, on their return to the east after a winter on the coast, Lewis and Clark, Sacajawea, and the rest of the Corps of Discovery traversed through what is now the property on an old Indian road. Clark’s journal for the day’s travels states, “we took leave of these friendly honest people the Wollahwollahs . . . and . . . continued our rout through an open level sandy plain to a bold Creek [now called the Touchet River] 10 yds wide . . . there are many large banks of pure sand . . . drifted up by the wind to the height of 15 or 20 feet, lying in many parts of the plain through which we passed today [sic].” These banks of sand are still visible today, referred to by the Plucker family as “the dunes.”

In 1855, according to journals of the U.S. Army, on a hillside on the farm overlooking the Touchet River, Chief Peopeomoxmox of the Walla Walla tribe gave himself up under a white flag of truce to troops of the Oregon Mounted Volunteers to allow his encamped tribe time to escape. Days later, the soldiers and Indians began the four-day Battle of Walla Walla/Frenchtown, leading to the Chief’s unfortunate and infamous death.

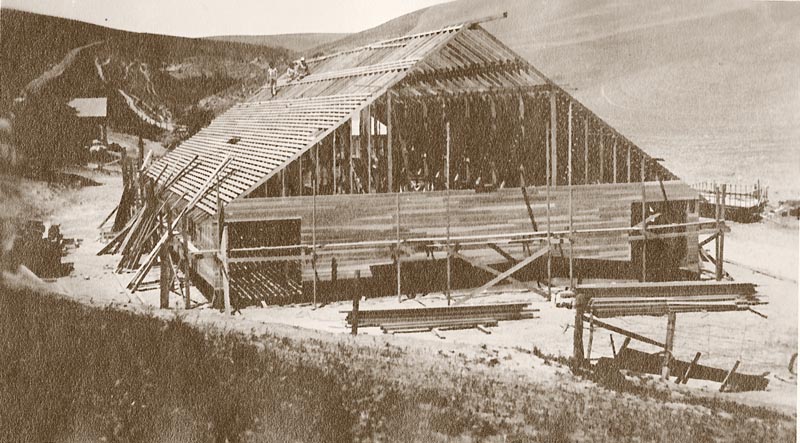

The Plucker Barn under construction.

In about 1920, after the original barn had burned down, Charles’ son, Fritz, built the current barn to house the workhorses and store the feed, hay, and tack needed to support the teams required for all of the pull-machinery. Robert, the third-generation owner and patriarch of the family, remembers having to wake early and feed the animals and milk the cows in the barn, and couldn’t wait until his dad, Fritz, “modernized” with self-propelled machinery. Robert’s boys and daughter grew up stacking hay bales in the barn and tending to 4-H horses and cows. In the early 1980s, however the barn became more of a place to store “stuff,” filling up with old parts, discarded appliances, lumber—basically, anything and everything under the sun. Despite this, it was still a place for the fourth and fifth generations of Plucker kids to explore in hopes of finding “treasures.”

The Plucker Barn in 2015, prior to receiving a Heritage Barn Grant.

In 2015, with the barn nearing 100 years in age and becoming more and more dilapidated, Robert applied and was accepted for a Heritage Barn Grant in the 2015-2017 biennium of the Washington Capital Budget. As the bids to do the work came in from various sources, it became apparent as to the size and scope the project would entail. One-half of the siding of the 90×60-foot barn would need replaced, window frames and sashes would need to be rebuilt, all original hardware would need to be refurbished or replaced, and all of the doors would need to be rebuilt. Despite what appeared to be a daunting task, the family realized that they could do the work better and for less money if they did the work themselves. Extensive research led to Eric Sederburg of Eastern Oregon Custom Milling. He was able to source and mill the same vertical grain wood siding they used a century ago and rebuild the windows. The original metal hardware for the barn rails, handles, and rollers, all rusted to what appeared to be complete disrepair, was sandblasted and painted by Custom Coat in Pasco, to appear as new as they were 100 years ago. With the grant and needed materials secured, it was then up to the family to do the hard work.

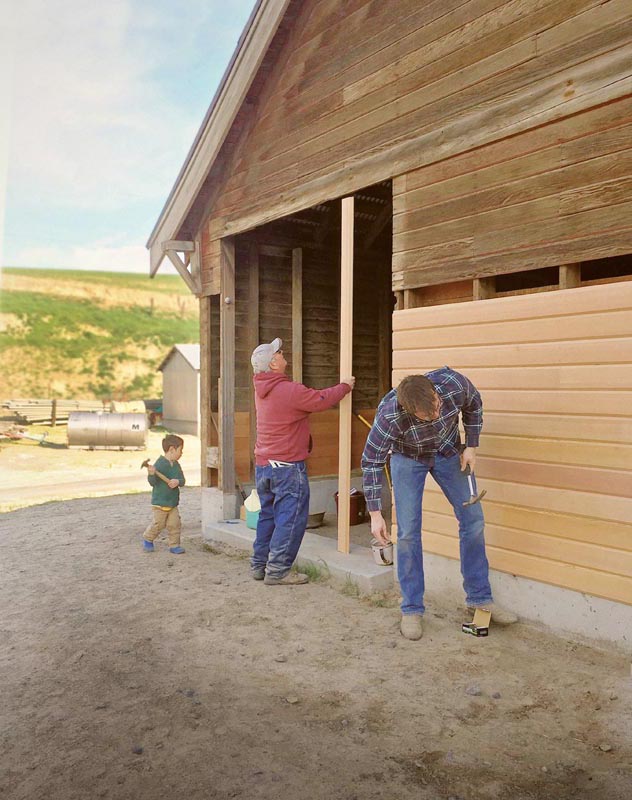

Cooper, Scott, and Cober Plucker at work on the south side of the Plucker Barn in Walla Walla County.

In April 2017, no fewer than 12 family members, including brothers, sisters, grandkids, cousins, and spouses, took up the task to tear out the old and put up the new. Lessons were learned and treasures were found. While tearing out one side of the barn, up to 12 “petrified” chicken eggs were found in perfect condition surrounded by old hay, presumably placed there by a pack rat over six decades ago. All of the missing door handles and rollers were found hidden beneath years of dirt and old, hard cow- and horse-pies. A jig was built to build the doors and fit them in place. The old nails were placed in an old wash pan, and by the end of the project it was filled to the brim. The nails are now used by all the great-grandkids to practice their nailing into an old stump. Half-round period gutters were installed to prevent water damage to the foundation, snow-guards were added to the roof to prevent snow slides along the sides of the barn, and new period-style lighting was added to make the barn workable at night.

Family photo op after the first barn door was installed with Nick, Ron, Robert, Scott, and Cathy Plucker.

After three months of work, the barn was ready for a fresh coat of paint. Worried that the original paint might have lead properties, testing determined it to be lead free, saving time and money. Through expert consultants from the Spokane area, it was determined to use a slow-dry primer and paint suitable for both old and new wood. With the family settling on Sherwin Williams’ “Heritage Red” and “Extra White,” the barn now stands in all its past glory. Finally, the entire inside of the barn was cleaned out, with only the old horse-drawn tack, antique farm equipment and memories remaining, with new memories of future generations to come.

For Robert, as huge as the barn project was for the family, and as dramatic as the change of the barn from a dilapidated structure to again the centerpiece of the farm, it was how the family came together during that time that made the project worth every effort. Every minute of work on the barn was looked forward to by every member of the family. In fact, Robert’s youngest grandson, three-year-old Cooper, learned a valuable lesson: while pounding an old nail back into the framework of the barn, much to the chagrin of his father trying to remove the nails, he observed, “If you work hard you make money.” And in this case, you make memories.

Interior of the Plucker Barn which now houses farm equipment, including some antique pieces.

A restored window on the Plucker Barn. The slight variation in the texture of the siding differentiates the old from the new.